Times Like These

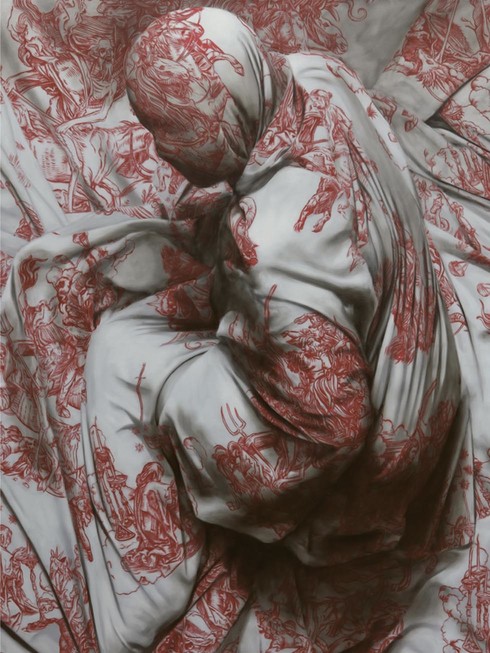

Written by Ulrika Lindqvuist by Janae McIntoshIn her debut novel, The Ministry of Time, Kaliane Bradley blends history, science fiction, and an inti-mate exploration of migration and belonging. The novel follows time-travellers displaced from their respective eras, thrust into modern Britain, and forced to navigate their new reality under the watchful eye of a mysterious government ministry. In this

conversation with Ulrika Lindqvist, Bradley discusses the emotional heart of her novel, the complexities of language, and the personal inspirations that shaped her storytelling. From British polar exploration to generational trauma, and even her admiration for Terry Pratchett, Bradley offers insight into her writ- ing process, the themes that drive her work, and what we can expect from her next book.

Ulrika Lindqvist: The Ministry of Time covers time- travelling and early on in the book, the narrator states that we don’t need to know how this

works, is that a way for you to not go into the sci-fi elements or physics too much?

Kaliane Bradley: Exactly, so even though I was very interested in the sci-fi tropes it was important to me that the book was understood as someone’s emotional journey. So I wanted to foreground the emotional journey of time travellers rather than the physics of time travel and the kind of hard sci-fi prospects of time travelling. And that’s not because I don’t enjoy reading about that but I think it wasn’t what I wanted to focus on for this book. And so, it’s a slightly cheeky way to signal

to the reader early on “Sorry this isn’t straight science fiction, you’re getting a mixture of genres here”.

UL: There are so many themes going through this novel but one that stood out to me was linguistics. A big discussion is what to call the migrants, which is the word used in the Swedish translation.

KB: That’s so interesting! In the English version, they’re called expats, which is a very politically loaded word. It’s generally applied to people from very privileged backgrounds in the sense that they can move wherever they want and return anytime they want, often in the UK it’s applied to white British people. Whereas there’s a conversation very early on in the book where they start arguing about the word refugee, one of the characters describes the time travellers as refugees, not expats because they can’t go home again. They have to stay here, they’re being pulled out of their culture, out of the life they had, and they have to assimilate - they’re refugees. And the ministry is very keen to make these people feel like no matter the time period they’re in, they’re British. And so, they’re only ever expats. It’s propaganda to persuade them to assimilate and to persuade them to accept 21st-century Britain as their home.

UL: That’s what is really unique with this novel, often you can tell how important language has been to the author but in this novel, the language is actually discussed within the story. Another thing I found interesting is when Commander Graham Gore realises that his private correspondence has been read by the ministry and feels uneasy about that, what inspired this storyline?

KB: I started writing the original version of The Ministry of Time for some friends. During lockdown, I got very interested in British polar exploration. And because of the lockdown, I couldn’t go anywhere, I couldn’t research and so I found this online group of people who were also polar exploration enthusiasts and we all followed a TV show called The Terror about British polar exploration and they were so generous, they shared their research with me and really made me feel welcome, so I started writing the book as a sort of playful gift to them. So, the very first version of the novel was written for people reading the private correspondence of these polar explorers or their diaries. One of the first things I was given was a scan someone had taken of a polar explorer’s diary and it’s just so strange to have that level of access to people - to be able to see someone at so many points in their life, confessing to things so privately, different letters to different people. In life, when you meet someone you don’t have that level of access. But the level of access that the ministry is given when it comes to Graham is incredibly unusual and makes him feel like he’s being studied because it’s weird for someone to have read your private correspondence that’s being exhibited in a museum. I think we felt both romantically about that but also maybe guilty. It’s a strange feeling; historical and biographical research. Feeling so close to the person you’re studying but they will never know you. It’s one of the frictions in the ministry that I try to convey in the book, that it can be almost depersonalising, alienating to study someone who feels intimate but you don’t know them intimately if you’re just studying their old letters because you’re not trying to connect with them.

UL: Graham is the only character in the book that’s based on a real person, and I found myself googling a lot. I think a lot is commonly known in the UK but as a Swede, I didn’t know of the Franklin Expedition, for example. Is it widely known internationally?

KB: I think it’s not so widely known anymore. It is one of those Victorian embarrassments that may have receded

into the past. By contrast, I think it’s very well known in Canada because the wreck is there. Margret Atwood apparently is a huge Franklin Expedition fan. When I do book events in the UK, I get a real mix of people who are interested in the idea of a sci-fi book or romance book but don’t know about the expedition and then I had someone come to my event in Edinburgh wearing a badge that said “ask me about polar exploration”.

UL: Did you consider basing the other expats on historical characters or did you want to create them based on historical research?

KB: I just wanted to have a lot of freedom. Graham is great for creating a fictional character because we have so little material about him. He’s not important in history. He was important in the expedition but there just isn’t a lot of material which meant that I got to build his character from a very small number of details. With the rest of them, I wanted a certain amount of freedom to let them be the people I wanted them to be and what they might represent to a British reader. I think in the UK we have very preconceived ideas, especially about the First World War, about what a British officer was, or an Edwardian, or what a woman from London was like. And I wanted them to arrive on the wave of those preconceived ideas but then be completely different and be their own person entirely. And you can’t really do that when they’re tied to historical characters.

UL: Another prominent theme is generational trauma and migration, was it important for you to write about that?

KB: When I started writing the book, I invented the ministry just because I needed Graham in the 21st century because I wanted to play the game “What would it be like if your favourite polar explorer lived in your house?” But the more that I developed that story and the more that we talked about it, the more I started to see those parallels between someone who has been pulled from a different country and being forced to live in the UK and someone who has been pulled from history and has to live in the UK. The bridge narrator was originally not British Cambodian but just a kind of blank character because I wanted the readers to feel like she was them. But because I did start seeing this very interesting parallel, it was exciting and challenging to imagine someone’s mental state as a Victorian. To try to be psychologically realistic about what that would be like. I thought that it might be interesting for the bridge narrator to have a similar history so there is this parallel. Because I am British-Cambodian I thought I knew what character I could write well, I know what It feels like to be a member of the British Cambodian diaspora and I have a family history that I can draw on to enrich the text. I was also writing a different book at the time which I thought was going to be a serious novel that I never got off the ground but it was going to be about Cambodia and Khmer Rouge. And so, I thought there’s a character in there I think would work within the ministry so I’d like to take her out and I’d like to use her as this kind of parallel character. Because it became clear to me that this book that I was writing just for fun still provoked me into writing about the things that I think about all the time. Migration and refugees, immigration and assimilation. It seemed natural that it would occur in this book as well.

UL: What did the research for the book look like?

KB: For the Graham Gore segments, it was partly easy because I did just read a lot about polar exploration. I have this whole bookshelf of books about polar exploration and I drew on the information I learnt from different people’s research. But it was also very helpful to have access to the digitized letters, diaries, journals and illustrations drawn by men on the ground. They could express themselves closer to how I think Graham would have done. So I read a lot of stuff about the first exploration that Graham was on when he was in his 20s and then a lot about a later expedition. To get the language right for Margaret I cheated a bit, I read a lot of Shakespeare for fun, you’re always guaranteed a good time, but she might be talking in an older way because she’s later than Shakespeare, but I’m yet to be told off on it. I think the language for Arthur comes a lot from E.M. Forster because it’s the right time period and I think to hear the voice properly you need to be reading someone who’s writing in that time.

UL: If you could go through the door back in time, where would you go?

KB: Embarrassingly, I would probably go to the court of King James to see the first production of King Lear by Shakespeare because at that point he had written Hamlet and then he had three plays in the middle, which in my opinion were rubbish, so I have a feeling that maybe the audience at the time thought “Oh William Shakespeare, he wrote that really good play and now he’s run out of energy and is writing stupid comedies that aren’t very good and he’s lost his spark”. And I would love to see what it looked like when King Lear was first performed and they realised that he was still a genius. It’s my favourite play, I should say, I think that would have been wonderful. My only issue with going back that far is that I’m very short-sighted, I have to wear glasses so I don’t think I would have been able to see the play.

UL: Are there any specific novels or authors that inspired The Ministry of Time?

KB: The TV show The Terror was a major inspiration, that show is a great work of art and I wish it would have won more awards, it deserved it. I’m a huge fan of British fantasy writer Terry Pratchett, I love him and have read his books several times. I think was a genuine writer who believed in his characters, and their emotional reactions. He actually wrote a book where a man was pulled back in time. I’m not even sure how much Terry Pratchett has influenced me because I read him so

much, and love him so much.

UL: What does your creative process look like?

KB: I believe that the greatest writers are morning people, I don’t do that. I wish I could, I think I would be a better person morally, as a writer, socially if I got up early in the morning and ate a big breakfast and then wrote. But I’m very lucky, I work from home part of the week and write when I basically have my evening commute, or I write very late in the evening, after procrastinating just to realise how much I love writing.

UL: What’s next for you as a writer?

KB: I’m currently under contract for my second book and it’s going to be very different from The Ministry of Time. I keep describing it as a neo-noir fantasy, it’s partly set in the land of the dead and partly in contemporary London.