“When I paint, I enter this world as an explorer and the painting process becomes a journey of discovery,” says Swedish artist Markus Åkesson. His artistic journey is steeped in myth and magic, serving as a portal to a world where reality and dreams intertwine, the familiar becomes uncanny, and beauty is tinged with an undercurrent of unease.

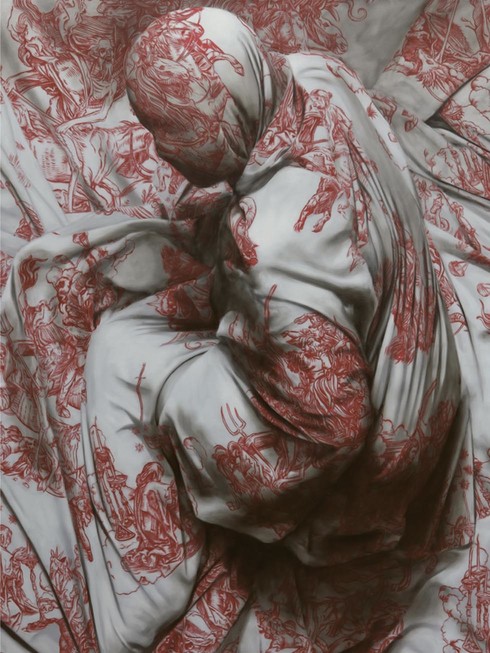

From an early age, Åkesson had a passion for drawing and developed an interest in motif painting during his teenage years. His artistic talent was first nurtured in his initial career as a glass engraver, a craft that fed his interest in light and texture as well as shaping his meticulous attention to detail. Although Markus has no formal training in the evocative and technically sophisticated realistic painting that has come to define his work, he is deeply fascinated by patterns. He draws inspiration from pattern cultures around the world and creates his unique designs. Using a refined and surrealistic method, he skillfully integrates these patterns into his paintings.

Drawing from a rich tapestry of influences, ranging from Old Master paintings and medieval symbolism to Scandinavian folklore and alchemical traditions, his pieces, whether they depict solitary figures suspended in time or taxidermied animals frozen mid-hunt, are imbued with quiet tension. His paintings and sculptures invite viewers into liminal spaces, where the boundaries between life and death, past and present, and the tangible and the imagined blur.

Natalia Muntean: Your work often explores the boundary between reality and dreams. How do you navigate this boundary and how do you decide when a piece has successfully captured that tension?

Marcus Åkesson: In my work, this liminal space between reality and dreams has always intrigued me. It is an “in-between” state, which reflects transitions such as the passage from childhood to adolescence or the moments between sleep and wakefulness. When I paint, I enter this world as an explorer and the painting process becomes a journey of discovery. I aim to create images that also allow the viewer to journey into this ambiguous space, perhaps offering a glimpse into another world. A piece has successfully captured this tension when it evokes a sense of mystery and invites personal interpretation.

NM: You’ve described your art as a way to “create a world where I want to be.” Can you elaborate on what this world looks like for you, and how it evolves with each new piece?

MÅ: I wouldn’t say that it’s one specific world, but rather that creation, or being in a creative process, allows any artist to explore ”other worlds”. This feeling of entering another space, or if we call it another world, forms a natural part of a creative process, which is intriguing and a big part of why I long to create. This also extends out to the physical workspace. My studio is more than just a place where I paint; it is an environment I have carefully curated, an attempt to a physical extension of the universe that exists within my paintings. It is important to me that my studio feels like a threshold, so when I come to the studio, I enter the space mentally as well.

NM: Your paintings are known for their incredible detail and texture, such as the intricate patterns in textiles or the play of light on skin. How do you achieve such realism, and what challenges do you face in rendering these details?

MÅ: Achieving realism in my work involves foremost meticulous attention to detail and the use of traditional painting techniques. My way of working with painting is centred around glazing; a traditional painting technique applied in realism, in which transparent layers of colours are applied over another thoroughly dried layer of opaque paint. However, when paying so much attention to details, one of the challenges becomes to maintain a balance between the complexity of the patterns and the overall harmony of the piece. All these details should enhance the narrative rather than overwhelm it.

NM: You often work with oil paints because of their versatility and depth. What is it about this medium that resonates with you, and how does it help you achieve your artistic vision?

MÅ: Oil paint's versatility and depth have always resonated with me, allowing for a rich exploration of light, shadow, and texture. I usually work on several canvases at the same time, and they revolve in the atelier. Some are drying, while I add new layers to others. Oil painting’s slow drying time offers the flexibility to build layers and make adjustments continuously.

NM: Your glass sculptures involve intricate techniques like glassblowing and gilding. How do you collaborate with master craftsmen, and how does this process shape the final piece?

MÅ: Collaborating with master craftsmen is integral to my work with glass sculptures. The glass industry was once very strong in my region, and even though much production has moved abroad, the glass expertise is still very much alive. The skills in glassblowing and gilding of the craftsmen bring a level of precision and artistry that is crucial to realizing my ideas. It’s a collaborative process that allows for a fusion of artistic ideas and skills, resulting in pieces that embody both my artistic vision and the craftsmen's technical mastery. It makes it possible to produce pieces that no artist could do alone because of the lifelong experience every technique requires, and that is fascinating.

NM: Your piece ”The Room of Life and Death” has been widely discussed for its haunting beauty. What was the inspiration behind this work, and what do you hope viewers take away from it?

MÅ: When I painted The Room of Life and Death, I was drawn to the moment when a child first begins to comprehend the existence of death, not as an abstract concept, but as something tangible, something inevitable. There is an unsettling beauty in that moment, a paradox I wanted to capture. The girl in the painting stands still, gazing at the frozen hunt before her, a fox lunging at a pheasant, its jaws wide open, claws reaching. It is a scene full of tension, yet there is no real movement. The wooden panel behind them reveals the truth: these animals are taxidermy, lifelike, yet lifeless. This is not a hunt, but a display of one. And this is where the idea of illusion comes in. The child sees what looks like life, but in truth, she is standing in a room filled with death. There is something hauntingly beautiful about the way death can be preserved, its essence captured, almost admired. In many ways, this is a reflection of our own relationship with mortality. As children, we encounter death for the first time with a sense of wonder, perhaps even reverence. But as we grow older, we are taught to fear it, to push it away. This painting tries to capture that fragile, fleeting moment before fear sets in—when death is still just another mystery waiting to be understood.

NM: ”Sleeping Beauty” sparked significant public debate. How do you feel about the role of art in society?

MÅ: Art possesses the unique capacity to question societal norms and provoke thoughtful discourse. The reaction to “Sleeping Beauty” underscored art's potential to confront comfort zones and stimulate conversations about cultural values and perceptions. Such dialogues are essential for societal growth and self-reflection. However, the reactions to ”Sleeping Beauty” and the decision to remove the painting from the school where it was hanging, were surprising to me. But I guess that it’s something I cannot ever control; how different audiences will react to, or interpret my work.

NM: You often use recurring symbols, such as gold, alchemic images, and esoteria.What do these elements represent to you, and why do they appear so frequently in your work?MÅ: Symbols have always fascinated me. There is something mysterious about the way they hold meaning. In my paintings, I choose symbols instinctively, guided more by feeling than by reason. There is no strict intellectual process behind them; instead, they emerge through intuition, through a kind of subconscious recognition. I combine them in ways that feel right, sometimes without fully understanding why. In this way, my paintings become a form of exploration. Sometimes, I am trying to understand something that I have not yet articulated, and the act of painting itself allows me to access that understanding. The symbols are not always meant to be decoded in a rigid way. They serve as entry points, both for myself and for the viewer. They open up narratives, suggest emotions and create contrast.

NM: Gold is a recurring motif in your work, symbolising transformation and alchemy. How do you use gold to enhance the narrative or emotional impact of a piece?

MÅ: Gold has always held a deep symbolic weight for me. In alchemy, gold represents transformation, the ultimate state of refinement, of transmutation from something raw into something pure and eternal. That idea fascinates me, the notion that matter, through a mysterious process, can become something transcendent. In many ways, painting itself feels like a kind of alchemy, turning pigment and canvas into something more than just an image, into something that holds emotion, memory, and meaning.

NM: You’ve cited Old Master paintings as a significant influence on your work. How do you reinterpret their techniques or themes in a contemporary context?

MÅ: I have always been drawn to medieval themes in art, particularly the Danse Macabre, or the Dance of Death. There is something deeply human in these works, the way they depict the inevitable fate that unites us all, regardless of status or wealth. Medieval artists had a way of portraying death not just as an end, but as a presence, an inescapable part of life itself. I find that perspective both haunting and beautiful. When I incorporate these themes into my own work, or even directly reference elements from medieval paintings and woodcuts, it is not simply an act of homage. It is an attempt to see the world as they saw it, to step into their mindset and to understand how they perceived existence. By borrowing their imagery, sometimes even copying specific details, I try to engage in a silent dialogue with the past. It becomes a way of experiencing their fears, their beliefs, and their aesthetics from within, rather than just observing them from a modern standpoint. What fascinates me most is how these old images carry a dual nature: they are both dark and strangely playful. The skeletal figures in the dance of death do not simply stand as grim reminders of mortality; they dance, they move, and they engage with the living in a way that feels unsettlingly intimate. It speaks to the way we try to negotiate with mortality, and how we dress it in symbols and rituals in an attempt to understand it.

NM: You mentioned being inspired by literature, film, and music. Can you share a specific book, film, or piece of music that has profoundly impacted your art?

MÅ: One of the most significant literary influences on my work is the collection Among Gnomes and Trolls, illustrated by John Bauer. This book, filled with Scandinavian folk tales and myths, captivated me during my childhood and sparked my fascination with drawing. The mystical forests and mythical creatures depicted by Bauer continue to inspire the themes and atmospheres in my paintings.

NM: You describe your art as a continuous exploration of new ideas and techniques. Are there any new themes, materials, or methods you’re excited to explore in the future?

MÅ: I am currently delving deeper into the interplay of patterns and art history by integrating motifs from the Middle Ages with floral designs. This exploration involves creating unique textiles based on these patterns and incorporating them into my paintings, allowing me to blend historical references with contemporary aesthetics. I’m also very excited about one upcoming project with Kosta Boda, a series of figurines that will be launched this autumn. It’s a project that feels deeply personal to me, not only because of the craftsmanship involved but also because of my own childhood fascination with porcelain figurines. I collected them as a child, completely mesmerised by their delicate details and the small worlds they seemed to contain. I never visited art galleries as a child, I didn’t come from that kind of background. But I did grow up surrounded by objects that told stories, small treasures that held meaning in their own way. That’s part of what draws me to this project. It’s an opportunity to create something that can connect with people in a different way, outside of the traditional art scene. Something that carries the same sense of mystery and beauty as my paintings but in a form that can be held, collected, and lived with. There is an intimacy to that that I find beautiful.

NM: If you could go back and give your younger self one piece of advice about your artistic journey, what would it be?

MÅ: I would encourage my younger self to embrace patience and trust in the process. Artistic growth is a journey filled with exploration, experimentation, and occasional setbacks. Embracing each experience as a learning opportunity and remaining true to one's vision are crucial for developing a unique artistic voice.