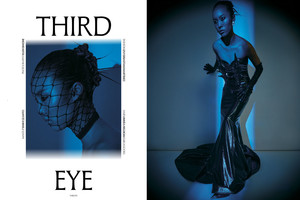

The Commodification of Christ

Written by Philip Warkander by Michaela WidergrenThe expressions of contemporary fashion – as a cultural, social and financial phenomenon – are characterized by two great paradoxes. The first concerns the connotations of the actual fashion artefact in the shape of a garment; it is simultaneously a commercial commodity (and as such part of a global market economy) and part of someone’s personal life, integrated in someone’s everyday existence. The garments we wear communicate to others in a multitude of ways, while at the same time being affected by experiences and charged with emotions and memories.

The other great paradox is connected to the very core of fashion itself, its constant need for reinvention. Fashion is characterized by a strong need to continuously change its appearance; organized through the temporal flow of fashion seasons (though lately this system is spinning so fast the seasons now are almost blurred, new collections appearing online already a year before the actual garments reach the shops).

The relation between fashion and time creates a need to articulate the contemporary. This is done by questioning the ingrained, breaking social taboos and undermining the normative.

Think, for example, of Chanel’s reinvention of luxury goods by using jersey and mixing diamonds with glass stones, or Yves Saint Laurent’s female version of le smoking, creating a new silhouette for women.

However, at the same time, the dominance of fashion in contemporary culture also makes it a strongly conservative force, whose sartorial expressions create distinctions between the same categories it claims to undermine. Fashion determines how femininity should be aestheticized, and through its distinction between high street and high fashion, it enforces the differences between the poor and the affluent. This way, fashion simultaneously questions and reinforces the notion that gender, class and lifestyle are defined through sartorial differences.

Fashion can thus be said to hold multiple dimensions, existing side by side. Some are aligned with each other while others have a paradoxical relationship, at times even operating as each other’s opposites. Because of this, fashion is the most culturally charged form of expression of the modern era; carrying the possibility to strengthen normative forces while at the same time threatening them, conflating macro economy with artefacts of the personal and private.

Many designers are aware of fashion’s paradoxical double-nature, deliberately interlacing personal references with commercial expressions. The Italian design-duo Domenico Dolce and Stefano Gabbana have for a long time incorporated – both into their sartorial creations but in particular in their jewelry design – the Catholic aesthetics of their home country. The figure of Christ, gold crucifixes and other religious symbols have been incorporated into embroideries, and turned into overtly sexual necklaces and large, luxurious earrings, combined with the famous Dolce&Gabbana-logotype. The Catholically charged aesthetics are thus distributed internationally as a fashion commodity.

Another example of this practice is French designer Christian Lacroix, who successfully reworked the Christian cross of his childhood into a symbol of his luxury goods.

The opulent cross is now intimately connected to his fashion brand. His fellow-countryman Jean-Paul Gaultier seems equally fascinated with the legacy of Catholic imagery and symbolism. Focusing on the female icons of Christianity, he has transformed religious artworks and turned them into corporeal versions of the holy women of the Bible. Designing intricate sets of dresses, jewellery and entire halos around the models’ heads, the young women appeared on his catwalk as if it were a church aisle; Christian archetypes materialized in flesh and blood. The dresses were the colour of church glass windows and in his S/S 2007 collection, the models posed in front of a heavenly staircase, as if directly descended from heaven. The Christian symbolism was transferred from churches and cathedrals to shops and department stores; the style of the holy Madonna now possible to purchase, to wear to dinner parties and nights out on the town.

Gaultier’s childhood memories from Catholic France became interwoven with his present career, brought to life in a context where they would act as novel commodities instead of eternal symbols of belief.

Also Givenchy’s Riccardo Tisci has sought divine inspiration, creating gold necklaces in the shape of the thorn crown of Jesus. When this ancient symbol of his humiliation and degradation is re contextualized within a contemporary fashion discourse, it is transformed into a costly and conspicuous symbol of consumption.

The Christian connotations are combined with the logotype of a French couture house, the thorns now made out of precious metals. This way, Catholic imagery in high fashion both questions ingrained notions of what is sacred and holy, while at the same upholding class boundaries through the exclusive prices.

The transformation of Christ into a commodity has become the ultimate sign that fashion and shopping is the religion of modern life.