Spoiled Image - Photography Unbound at Konstnärshuset

Written by Natalia MunteanIn Spoiled Image, photographers Sofia Runarsdotter and Diana Agunbiade-Kolawole surrender their archives, professional and personal, artistic and accidental, to reimagining. Stripped of original intent, their images mesh and collide, freed from categories like photojournalism, fashion, or private snapshots. Here, a forgotten self-portrait, a celebrity snapshot, or a Tokyo train sequence demand attention not for what they were, but for what they are: singular, unresolved, and electric in their new dialogue. Curated by Ashik Zaman, the exhibition is part of a broader focus on contemporary photography and runs from May 10 to June 7 at SKF/Konstnärshuset. What happens when we stop labelling images and simply let them speak?

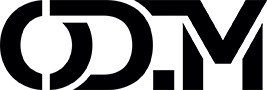

Sofia Runarsdotter

Natalia Muntean: Your Girl Battle series captures raw, physical tension between women. In Spoiled Image, how does this visceral approach translate when your images are divorced from their original narrative context?

Sofia Runarsdotter: Girl Battle is a personal project, photographed in my home village. From the outset, the selection and presentation of the photographs in the Girl Battle series were intended to be experienced both as a whole and as singular photographs. I did the selection together with curator Ashik Zaman. Our aim was for each final image to be so powerful that it could stand alone, independent of its original context. In this exhibition, the photograph Spider is shown in a new context, which brings fresh energy and opens it up to new interpretations. I believe that change and transformation are positive forces. The motif, to me, represents something far beyond sport.

NM: The exhibition pulls images from your personal and professional archives, even snapshots never meant to be shown as art. How did this process of recontextualization change your relationship to your work? Were there photographs that surprised you by gaining new meaning when freed from their original purpose?

SR: I have an archive spanning over two decades, comprising approximately 300,000 photographs (though that figure is admittedly an estimate). These images were captured with a variety of cameras and stored across multiple formats: CDs, hard drives, and negatives. When Ashik invited Diana and me to do this exhibition, I anticipated the complexity of the process. The first step was to make a preliminary selection, a process that revealed how profoundly my way of seeing and reading photographs has evolved.

One particular photo stands out: a self-portrait taken in Slovenia in 2005. What struck me was how the passage of time had recontextualised the image. For me, it is saturated with personal memory, so much so that I could barely recall taking it. Suddenly, I was confronted not with a photograph, but with a younger version of myself gazing back. I found myself wondering: Could this image hold meaning for someone else? Might it resonate beyond my narrative?

This experience repeated itself with numerous photographs - images made in passing, never intended to be anything more than fragments. In that sense, the act of stepping back became essential. It was a relief, even a necessity, to allow a curator to engage with the work from a fresh perspective, unburdened by my associations.

NM: The title Spoiled Image suggests a corruption or subversion of expectations. What does “spoiled” mean to you in this context? Is it about disrupting the hierarchies of photography (art vs. commercial vs. personal), or is it more about the viewer's encounter with an image that refuses easy categorisation?

SR: I find it liberating when images are allowed to be seen simply for what they are - photographs in their own right, without being forced into predefined categories. Having worked in the space between art and photojournalism, I’ve often witnessed how powerful images, especially those by colleagues in similar fields, remain unseen because they don’t fit neatly into institutional or disciplinary frameworks. There was simply no room for them, no “appropriate” category.

With Spoiled Image, those boundaries are loosened. The images are no longer judged by conventional hierarchies or expectations, but encountered on their own terms. That openness allows for a greater generosity toward the image - a richer, more inclusive space of reception. In that sense, it becomes almost like a manifesto: a call to recognise the value of photographs that resist being pinned down.

NM: Does the Girl Battle image change meaning when separated from the full series and shown next to Diana’s work?

SR: I believe that when placed in dialogue with Diana’s archive, the Girl Battle image Spider gains a new and unexpected energy- one that I fully welcome. This kind of interplay has been a defining and enriching aspect of the entire process. It opens the work to new interpretations and connections that wouldn't have emerged within the original series alone.

NM: Were there old or forgotten photos that suddenly made sense in this exhibition?

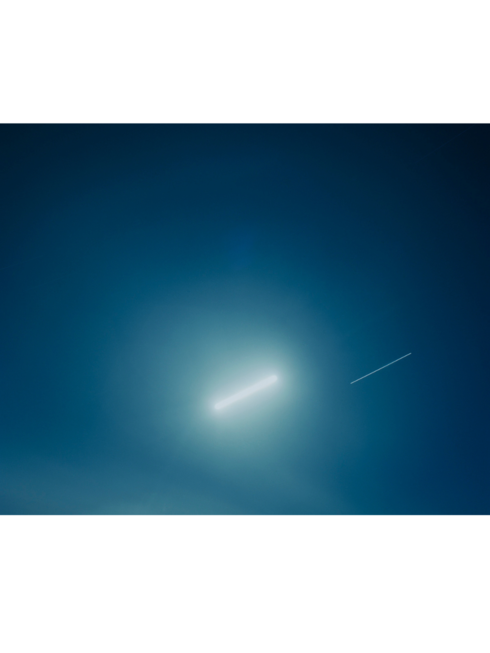

SR: They were, indeed. One example is a photograph I took in Tokyo in 2008, during a freelance assignment for various magazines. While going through my negatives, I suddenly came across a sequence from a train ride in Tokyo, images I had never seen before. And yet, as I looked at them, I began to recall taking the photo. Or did I? It's strange, perhaps I only imagined capturing that moment, projected the memory onto the image itself. The line between memory and imagination can blur so easily when revisiting old work. Ashik was immediately drawn to it. It’s just three exposures from that trip, separate from my digital files made for work, but they carry a distinct energy. There’s something timeless about watching the two children in motion, suspended as if flying. In a way, it mirrors the exhibition itself: a journey through time, fragments, and rediscovery.

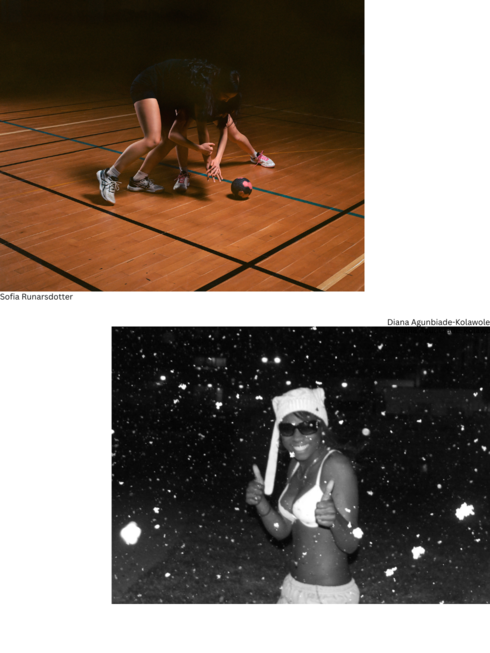

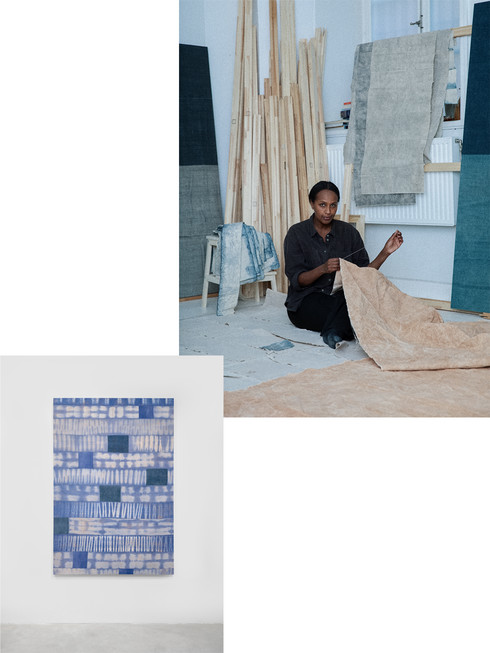

Diana Agunbiade-Kolawole

Natalia Muntea: Your work often documents Black diasporic communities. In this show, do these documentary images transform when displayed as fragments divorced from their sociopolitical context?

Diana Agunbiade-Kolawole: I think in the company and context, the images hold up and produce more questions than offer the expected resolution answers. My work is centred around lived experiences and as a Black woman in the West, making work on the spectrum of banality and sensationalism of existence, everything I do is political, even when they are placed out of context. To be impartial is also a political stance. I think the images individually may come under higher scrutiny because of this. The controversial scenario here is that Sofia Runarsdotter and I allowed this re-contextualisation to happen.

NM: Spoiled Image pulls images from your personal and professional archives, even snapshots never meant to be shown as art. Were there photographs that surprised you by gaining new meaning when freed from their original purpose?

DAK: Yes, the image of David. It is a full frame black and white portrait of my cousin flexing his muscles. We were at my grandmother’s place in the countryside in the height of summer in August. We often teased each other when we were all together; he was teased for being the shortest of all, even though he is the eldest. He was posing to show he was the strongest. I returned to the photograph and printed it together with the front image three years later. I was drawn to the two photographs, but I had no context in which to exhibit them. It just makes sense in this show, and it was one of the images Ashik, the curator, really connected with. In this exhibition, David becomes eye candy, and the image is transformed into a seductive image.

NM: The title Spoiled Image suggests a corruption or subversion of expectations. What does “spoiled” mean to you in this context? Is it about disrupting the hierarchies of photography (art vs. commercial vs. personal), or is it more about the viewer’s encounter with an image that refuses easy categorisation?

DAK: I think it is more about the encounter. The first image one is greeted with in the show is a photograph of Pharrell Williams that I took when I was 16 years old. It’s a cool image of a celebrity. It’s not the kind of work I am associated with in Sweden. There are also very personal family photographs that could be included in a retrospective or some sort but they would never be presented side by side. It is difficult to decide whether I feel there are hierarchies within my images; it is closer to whether I like them or not, if there is technical competency and other experiences I had when working with the images.

NM: A lot of your work tells important stories. When those images are shown without explanation, do you worry people might miss the point, or do you like the mystery?

DAK: I have used titles to help nudge the viewers in the right direction, but I think the viewers often enter and engage with their own lived experiences. Therefore, it is inevitable that they will read the images as they would like to, and engage with their own perspectives. As I have already experienced when we were making the selections for the show. It is also interesting for me as a photographer to have those interpretations of my work.

NM: The exhibition title suggests breaking the rules. Did you include any photos you normally wouldn’t show? Maybe something too personal or not “perfect” enough?

DAK: There are, for sure, some images I would not have shown in this way. I wanted to be as open-minded and allow Ashik to deliver his vision. When I produce work, I already know the print size and output elements, as they have a great impact on how the work will be in the end. In this case, some of the size choices are not technically perfect in the traditional photographic way, and I like that. The elements are pushed to their limits; there is too much noise and grain, and that is quite fun. Very liberating. There is a self-portrait that was maybe on MySpace, which ended up in the show. Whilst I also had to find solutions for images that were digitised a long time ago, where I don’t know where the original negatives are. Naturally, I would have edited them out, but in this show, they are present.

Photos by Sissela Jensen