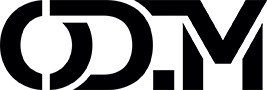

An interview with Minna Palmqvist

Written by Michaela WidergrenI meet up with Minna at her studio just outside of the city, next to the well known art space Färgfabriken. We sit down in the large old factory that’s now her office, and has been so for four and half years and start talking while drinking coffee out of neon bright yellow mugs. I’ve been a fan since the last collection, which she remembers, “Weren’t you the one who came up to me after my show last fashion week and said you loved my work?”. Yes, that was me.

MM: First, can you tell me about your latest collection, SS14?

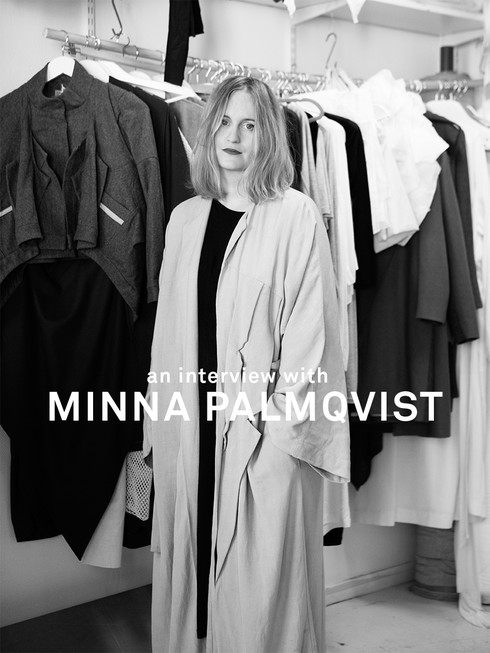

MP: I start working on my new pieces from the same basic idea as previous collections and garments, which is the female body and how it is presented, the chaos around it and how the fashion industry is constructed. This time I focused on having an actual show… I think most people know me for working with conceptual art installations and hand made show pieces. I have actually worked also with ready-to-wear for a long time, and I felt it was time to show this to the fashion audience. I started thinking about problems concerning people’s everyday wardrobe, for example women struggling to get in to smaller sizes, so then I made cracks in the garments to give the body room, I wanted the body to claim it’s space. It’s much about cracking up and brimming over. I’m still working with quilts, running over and leaking through seems. I don’t want the body to be captured inside the clothes. The AW14 collection is a continuum of the movie I made a year ago that was based on breaking down and building up garments and looks.

MM: Was that when you started making the fat cell like patterns?

MP: Actually no, I started working with that in 2009, at first is was more of an art project for the show pieces but then I started bringing it in to the ready to wear as well. Some people think it looks gross, and I guess it does in some ways, but that’s what I like bout it, I like when you can’t really make up your mind if it’s beautiful or disgusting. For example I’ve worked with swarowski crystals used as sweat stains, that’s one method I’d like to evolve and work more with. I think a lot of what we consider ugly could easily be transformed in to something beautiful.

MM: When I’ve read about you, you’re often portrayed as being strongly political, are you?

MP: Hmm.. I guess I am. In the beginning of my career I didn’t think like that. I think I was afraid that if I’d state being political I’d be taking to big a words in my mouth. But now I know better - the way the world and the fashion business is looking today, how can you not be political? Politics doesn’t have to be about talking, writing and knowing most, but about doing and thinking, making active choices. There’s politics in both our private and public lives, everything is intertwined. So I’m political, there are things that I believe is wrong and that I have strong opinions about, for example the differences between sexes. Women are still being judged by their looks and not by their competence, and that is being political.

MM: Is it hard to be political in the fashion industry?

MP: No, I don’t think so, well, some people think I’m being pretentious, they just want me to make beautiful clothes. Which I do so it’s not the garments themselves that are political it’s my driven force, I find inspiration in my frustration. I’m surprised over how much focus has been on my creating process, I feel as if people are in the mood for politics.

MM: I’m sure a lot of people would like to be political but don’t have the courage.

MP: There’s a lot of times I get stomach aches after saying something “political” because I’m better at forming objects than expressing myself in words, but on the other hand I feel as if we need to discuss those things, people need to start talking.

MM: Are you afraid to say something “wrong”?

MP: I used to be really afraid of that, but then I started thinking, what’s the worst thing that can happen? Maybe someone will question what I said and maybe I’ll realize I was wrong. Everybody has a right to be wrong sometimes. I’m not always comfortable to make political statements in words, as I said before, although I like to discuss politics as we are doing right now. I’ve come to realize that’s one of the reasons I work with design. It’s a silent way of being political.

I start thinking about the runway show Minna presented, the show itself was what you would call political. She used models in different sizes and ages, which sometimes happens during fashion week, but is still clearly a statement, the reviews were great.

MM: The SS14 collection and runway show was received really well, what has happened since?

MP: I know, that made me really happy. I wanted to show runway and ready to wear looks because that’s the world I’m in, and at the same time I felt as if my small changes mattered, using the women we did. Mixing typical models with untypical models on the runway is something that I hope to do again, and preferably in a larger scale. Because of economic reasons I actually can’t make my first samples into so many sizes, since the same samples need to work for both show and press, and press usually wants to borrow size small for their shoots. I also liked the fact that the models came in to the runway together, showcasing them as equals. And it made me even more happier that the people watching and taking part of the show appreciated those small efforts of change.

Going through the runway show in my mind, I remembered taking notice of the white crystal covered sneakers worn by all of the models.

MM: Were’d you get the shoes from?

MP: Oh, the shoes are from LA! But the bling bling was put on in the studio for the show. My stylist Nicole Walker was there during the summer, we e-mailed about different styling ideas and both agreed on that the models should wear sneakers. It felt pretty good.

MM: Are you wearing them now?

MP: Yes :)

MM: Did you ever think about making shoes yourself?

MP: Oh my god yes, I think about it quite often, shoes are so much fun. I just started making bags which is a bit more easier to produce, it’s a great product since it doesn’t have to come in different sizes. There’s just one bag size for all body types.

MM: The fabrics you use are quite stretchy and also a lot of your garments are loose to the body, is this to make them fit different shapes?

MP: In some ways it is, but it’s also a personal preference. I don’t want the garments to be restrictive. For example, I’ve tried on jackets and coats with my friends and a lot of the times they garments fit around the shoulders but not around the waist. That says something about the size system to me, I mean, I don’t think that it’s just me making friends with women that has large bottoms. Those are the kind of things that I try thinking about when I’m creating new pieces.