Joel is no stranger to dwell in the unknown. The praised songwriter, 26 years of age, switched behind-the-scenes production for on-stage, immediate happenstance. Here, he freely ponders characteristics, perspectives, and visuals – embodying an enthralling admixture of fact and fiction.

Born in the Colombian capital of Bogotá, forming part of the Andes, then raised in picturesque, Astrid Lindgren-home of Vimmerby, Joel is familiar with change. His personality is vibrant, seemingly rooted in a series of events continuously merging heartfelt and challenging. Truthfully, his introduction to (him)self aligns with this thought, the most notable, idealism meets realism passage being; “I am quite a mediocre DJ, ride my bike almost everywhere, and just got a deep vein thrombosis although I run a lot and eat worrying amounts of broccoli.”

Music first struck him at the age of 8. “That is when I started playing the flute. It quickly evolved. I have always had a profound love for music, teaching myself how to play both the piano and guitar,” he says. For the foreseeable future, music served side business. If we fast-forward, Joel still perceived his musical endeavors as strictly part time when applying for university. “I opted for a gap year before starting my studies at Uppsala University. I wanted to study music. But before even making it to university, I got a deal with Benny Andersson’s (ABBA, mind you) publishing label RMV. The gap year has continued ever since.”

The initial phases of Joel’s career path looked, all industry norms considered, somewhat different. His songwriter self dominated, collaborating with numerous Scandinavian artists of the moment, from The Mamas to Wiktoria. “Once I decided to finally release music myself I think I managed to dodge quite a few bullets. Observation became key, witnessing other up-and-coming artists falling into traps, challenges, and hurdles prone to appear at an early stage”.

Naturally, discussions arise about the method of transformation. Embarking on new, previously unknown paths and how transcendence feels in the first place. “Usually, your first year being a signed artist consists of constantly working with new people. Every day. It easily becomes draining, regularly open yourself up to strangers. I had another kind of luxury, privileged to focus on producers I already knew, and speeding up the writing process instead of figuring out the ideal constellation of writers.”

Joel’s own musical catalogue is equally perspective-altering. When asked about characteristics, he points at a much familiar, general consensus of all writers out there. Simply put, a common interest, often an end goal, to eternally engage through emotion. ”Two years ago, I re-read Amy Poehler's autobiography. I realised that script writing isn’t much different. Writers of all genres share an urge to always convey a feeling, the feeling that hits you hardest in the gut. I want the listener to be on edge, experiencing what I felt when writing. Writers like Karin Boye, Mike White, and director Wes Anderson inspire me greatly.”

In June 2022, Joel released his inaugural EP, Where the tragic happens. He paints up a familiar scenario, explaining how he regularly enters a strong, writing infused head space as something notable happens in life. High’s and lows. The example provided; is early 2022, being dumped for the first time, another bustling Covid-19 wave hits. Yet, transcending into a surprising ode to a reassuring safe space – one’s home. “I brought my studio setup home. Started writing aimlessly. The songs felt too personal to pitch, so I decided to write for myself. On my terms, when inspiration hit me. My EP blossomed during 3-4 months, constantly writing in the kitchen. I had cereal and grilled cheese for weeks straight, allowing myself to solely operate on wants. I hardly left my apartment. It became a home, the walls seeing the very best and worst of me.”

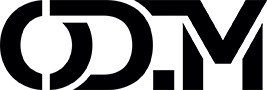

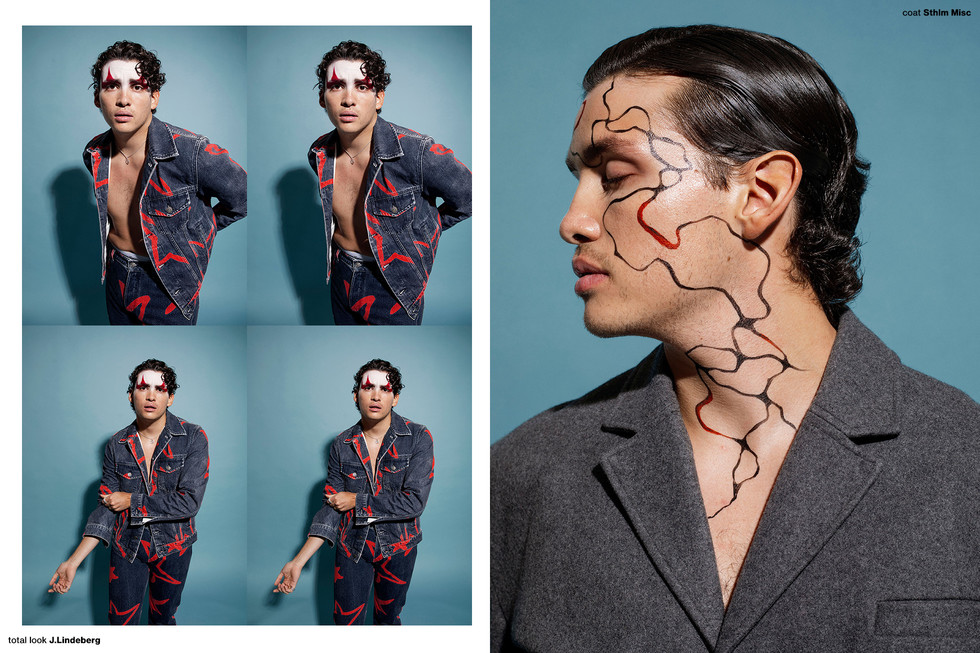

Production aside, Joel is equally aware of visuals. His fashion, more specifically, is more than just randomised, spur of the moment picks.

LINNÉA: I get the feeling that you’re quite keen on fashion. How would you best describe your visual aesthetic?

JOEL: I and my friend started naming our styles on a twice a year basis. Think seasonal fashion, with the spring summer and autumn winter format. We did that to pinpoint how we wanted to dress that particular season. I've done that ever since. Last SS paid homage to the Ivy League college kid from the late 1980s and early 90s. This AW season leans toward the young Wall Street dad aesthetic, out on a stroll in the park on a Sunday.

My uniform is straightforward. Dad jeans or cargo pants, snug t-shirt, baseball hat, chunky knits, often paired with sneakers and shirt jackets. Autumn and winter often feel more masculine for me, while feminine influences dominate during spring and summer.

L: Feels like you have some inspirations in mind.

J: Kerby Jean-Raymond never fails to impress. I'm constantly inspired by what he is making at Pyer Moss, referencing trauma and New York City-grit in the rawest, ethereal of ways. Harry Lambert is another one, a stylist with an inspiring and surprising eye.

L: Returning to music. You have spoilt us quite a bit with new material in 2022. What lies next on the horizon for Joel?

J: Honestly, I don't know. This business is run by maybes, and the right song at the right time. Trust me when I say that I have been in the studio, writing about recent heartbreaks, and songs are coming together. Generally speaking, I am the worst at keeping my music to myself. I post some teasers on TikTok every now and then, so for the curious, do pay a visit. Fans, be excited. Exes, be wary. Haha.